The title of this post is perhaps a lie, when I think about “how to write.” Sometimes I feel like the more I write, the more I learn about and talk about writing, the less I actually know.

I’m guilty of many such searches:

“how to write a thriller”

“how to write a horror”

“how to write…. a book” (lol)

But the title intrigues me because it’s also what I like to read, so I really want to figure out how to write it — a vivid, wholly embodied protagonist that suffers from the same muddied, contradictory, impulsively difficult mindset that we all do. I say that with certainty because I think living with contradictions and impulses and strife is a universal experience and the reason characters can often fall flat to us on the page is because they don’t get to the core of this complexity. I don’t think it’s just me that’s lives with this. I think it’s all of us.

What is complicated anyway?

It’s difficult for me to define what a complicated female character entails, because mostly I can define it by what it isn’t — which is that, I can’t get inside her mind. When I think of an uncomplicated character, I think of the word redeemable. Often you’ll hear as a criticism that a character doesn’t have any redeemable qualities that make her relatable enough for a reader to keep going. What is redeemable, is it a character that takes life as it comes? Rolls with the punches? Is it a character who has some slight flaws but mostly seems to be a good person? Is it living at a lesser depth, refusing to question the self that drives you forward?

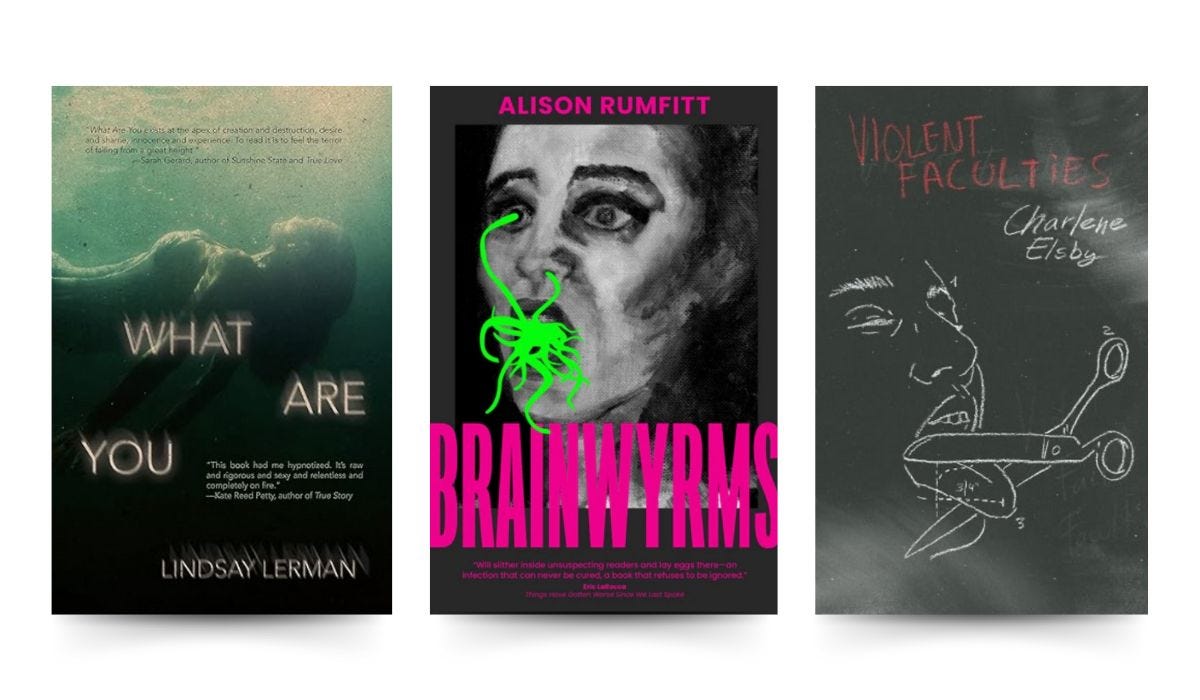

In What Are You,

explores the self through a majestic plural “you,” the many you’s one encounters in a lifetime. What Are You feels like the unwritten letters we want to send to everyone who has ever harmed us, forming new catastrophic caverns in our personality as a result, when she writes, “Each of you has shown me hell. That is, myself. You have shown me the conditions of my life, my existence.”The novel walks back and forth between our nameless narrator and a life lived with ‘you,’ splaying duress open like organs beneath a surgeon’s blade. The protagonist feels hard to catch, harder to define who she is, much like the novel itself, which is amorphous and prismatically changing in the tightrope dance of want versus not-want:

“I eat the world—Open, open, you’ve said, and I’ve listened—and I eat it and eat it, and it keeps leaving a bitter taste in my mouth. Replace it with something else, if even for a second. I’ll always be in trouble though, won’t I? Won’t I won’t I, because I see that I love your bitterness.”

In Brainwyrms by

, Frankie survives a TERF terrorist bombing at her workplace, struggling to cope when she meets mysterious parasite-obsessed Vanya. The ricochet between want, need, and denial working in Frankie’s mind are up front before the drama even happens, it’s how we meet her:“Coke would help probably. Coke would drag her back down to earth. That was the sort of thing a cokehead thought right before snorting some, but she wasn’t a cokehead, she didn’t have a habit, even if she took it every other weekend. It was every other weekend, after all. Every weekend and maybe there’d be a problem, maybe the girls would be justified in their little intervention scheme. She didn’t really know that was what they wanted, but she got the general idea of how they viewed her. They probably hovered more lines than she ever had! All this thinking about coke got to her. It was what she needed, clearly, or else she wouldn’t be thinking about it so much. But just when she turned towards the toilets with the intention of finding some twink to give her a bump, she saw Vanya for the first time.”

These characters demonstrate a specificity in their thought process that feel realistically impulsive, the tugging between Will I or Won’t I or If I Do It’s Fine Right? in attempts to move through rigid social mores. They show us the struggle of tightrope walking, so to write a complicated character means a writer has to understand the psychology of the person they’re creating — or at least flesh and feel it out as they’re writing her, which is half (or most) of the fun. Demonstrating the struggle elicits empathy for the right reader, or at the very least, wondering about the decisions she’ll make and where she ends up lets us fill in the gaps. Empathy can make a character somewhat redeemable to a reader, or make her relatable, even if unlikeable. But does it always need to be that way?

For me, the answer is no.

There doesn’t need to be anything redeemable about a character for me to keep reading. There only needs to be conflict, tension, and someone interesting to think about or an interesting mind to inhabit — the things that make a good book great. A complicated character seems to be someone whose inner conflict is apparent on the surface, and maybe this is what renders her “unlikeable” — doing, saying, or thinking the things that transgress the ordinary ways a person relates to the world. Or maybe the conflict isn’t on the surface because she shows no one — that’s a struggle, too. In fiction it means we’re lucky enough to experience someone whose inner conflict we can see up close. Even if their desires and motivations aren’t clear to them, or to the reader, what is clear is that the conflict exists and it’s working itself out.

Ultimately unredeemable is the protagonist of Violent Faculties by

, an academic so virulently lacking in empathy that one can only gawk in horror (the protagonist, not Charlene. I love Charlene). The first chapter of the novel opens with our spurned professor describing, through case notes, the many ways in which she tortured a woman named Emily through manipulating her enclosure and her size, measuring her victim’s desire to take up space both figuratively and emotionally.“When I put Emily in the closet and asked her (not explicitly) to adjust, she at first seemed amenable. She moved from side to side, just as she had in the room, and in doing so marked out various spaces in between which to move, which corresponded to differently cognized space. But unlike the room, which was merely somewhere to exist, the closet became somewhere to strategize. The space was not sufficient, and so Emily took to analyzing the space’s externality—the physical barrier marking off the space, in order to determine a way to move beyond it. She even took to dismantling the physical boundaries, clawing at the walls, and by doing so increased her allocated space to some small degree, though a futile effort it ultimately proved to be. She took no small amount of joy in reclaiming some amount of space from the drywall, even though with the drywall now on the floor, she had in fact not made any net gain of space but only succeeded in redistributing the space available, so as to be more to her liking. At this point in the study, I concluded it is not about increasing the available space to the subject, but the joy she takes in penetrating something that confines her, of destroying it, of rendering its spatiality undelineated.

We take joy in dismantling the boundary between what is something and what isn’t.

Once, before her captivity, when I’d made love to Emily, I said I would destroy her, and now I realized, this is what I’d meant.”

The professor nods to the similarity between Emily’s desire to destroy the boundary of the confined space and her own desire to destroy the boundary between Emily’s conscious and unconscious existence — that is, the body that keeps Emily’s mind tethered to this realm. I too find joy in dismantling boundaries, but maybe in less antisocial ways, like when I bake a camembert and break open the skin with a crusty piece of sourdough.

The professor doesn’t have a particular tightrope she’s walking that elicits empathy for the reader, but that’s what makes Elsby’s work in particular so compelling: what does it feel like to inhabit the mind of someone exploring the philosophical implications of humanhood through violent trial and error? What does it mean to kill? A revenge plot is by definition justifiable, but the driving arc of Violent Faculties is one of hoping the professor’s motivations become clear to us. Will she find the answers she seeks, and will we find the motivations justify the actions, or no? Can we make sense of this projection of hostility at the world? Will she defeat her god?

Authors like Rumfitt, Elsby and Lerman play on the unspoken rules of uncomplicated society by edging us deep into our disgust. Disgust is at its very essence what repels us—either through tactile sensation or through character. It cleaves into our own Jungian shadows by pinging on the personality traits we’ve rejected in our lives because we believed we’d be unloveable if we kept them: Someone who needs deeply, someone who hides their true feelings out of shame, someone who blames or lies without self-reflecting, someone who lets anger coil inside, or simply someone who gleefully plays on the visceral edges of desire without apology—even in writing these, they feel too simple because they don’t demonstrate the ways you can both want and not want, need and not need, fight and not fight, all at once. To disgust is the opposite of to attract. An emotional state that causes physical recoil, rejection not just of the person or experience that is disgusting, but discomfort so thick it makes you queasy by tempting total of rejection of what nourishes the self— that is, “this made me want to vomit.”

There is also desire, which doesn’t live parallel or even on a spectrum with disgust — I think they hold hands. This is where the beauty of internal conflict comes into play. They touch, then competing impulses fight against each other. What makes something disgusting, adorable, unhinged, irresistibly hatefuckable, justified or unjustified? How do we capture it enough that it feels real? The answer starts, at least partly, in exploration of the self. One person’s vomit is another person’s dinner (or maybe it’s both). Personhood is complex because our personality traits replicate, become repressed, and then betray us in infinite configurations. Probably the first best step is to begin to observe what lights up in you when you cringe at something complicated on the page, and ask yourself why it does that.

NEWS!

FEMGORE, the two hour workshop with myself, Charlene and Lindsay, is still enrolling.

A virtual seminar complete with generative writing exercises that explores writing the gruesome, saying what’s supposed to be left unsaid, and pushing creative boundaries.

We’ll discuss some of our favourite examples of writing that explore the beauty and brutality of femgore — from predatory characters to the philosophy of what repels society most about unredeemable or unlikeable female narrators and then together we’ll all write together, in the moment. You’ll leave with tools to help you write deep into disgust and elevate your work.

To register, send $100 to via PayPal to celsby@gmail.com (yes that is Charlene Elsby!) and write your name/email in the notes section. From here we will email you everything you need to attend the workshop. Class is Sept 1 at 12 pm PST / 3 pm EST/ 8 pm GMT. If you have any questions, DM me or reply to this email.

Goth Book Club! Writing sprint returns!

I’ve had to jumble some things around in my calendar this month as August and September are busy with travel and events.

Upcoming dates:

August 25, at 12 pm PST / 3 pm EST/ 8 pm GMT. We’re reading Triadic Intimacy by Emily Leon, a personal meditation on art, desire, and more (I need to read it to figure it out, its an enigmatic book) out from Inside the Castle.

September TBA: Love Letters to Dawn by Aileen Wuornos. We’ll be joined by author Nicola Maye Goldberg, author of Nothing Can Hurt You, to discuss this work and writing about crime-adjacent subjects.

The return of Brute Force

August 25, at 1 pm PST / 4 pm EST / 9 pm GMT after Goth Book Club, I’ll give you all a writing prompt and you’ll sprint write for 30-45 minutes and we’ll do a Q+A at the end.

Available to all paid subscribers. Zoom link goes out the day of. Yay!

Loved this, Elle! Gave me a lot to think about, thank you <3 It reminds me of Tampa by Alissa Nutting (about a teacher who grooms/molests her 14-year-old student, if you haven't read it). There's nothing redeemable about the protagonist and I was sooo disgusted and uncomfortable throughout the entire book...but I sure as fuck read til the end lol. It's a wild ride, which makes it interesting!

Really loved this piece. Excellent examples from some seriously talented writers. Saved it to read again and again. So stoked you're here, btw! Big fan of your writing. Deliver Me was phenomenal!